The 'Literal' definition of "Holodomor", is 'Death by Forced Starvation' Ukrainian........

Holodomor survivor accounts and memoirs:

"From 1 January to 22 April 1932, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine received 115 letters regarding famine conditions in Ukraine.................................

Among them were letters addressed to Stalin, which were returned from Moscow to Ukraine with orders to punish the writers as 'enemies of the people.'"

A. Full-length Memoirs:

~ Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust by Miron Dolot.

New York: W.W. Norton, 1985.

The author, a teen-ager during the time, presents a harrowing eyewitness account of the Holodomor as it was implemented and experienced in his village.

~ Sliding on the Snow Stone by Andy Szpuk. That Right Publishing LLC. 2011.

Particularly chapter 1, p.5-17, which recounts his childhood years during the Famine. From GoodReads reviewer 'Pam:' "This book is a recounting of a man's life in Ukraine during Stalin's genocide and his subsequent journey from the Ukraine with his father, running from both the Nazis and the Russian army, his life in between and the return to his childhood home when he was much older."

~ The Education of a True Believer by Lev Kopelev.

New York, Harper & Row, 1980 (Originally published in the US in Russian, 1978).

From the publisher's apt description: For Lev, a committed communist activist, "The discrepancies between that belief and what his own experience shows him culminate in a great chapter of lamentation: 'The Last Grain Collections (1933).' But here too, he maintains the perspective of that time: The Bolsheviks who ravage the villages are presented as colorful characters, self-sacrificing workers....But now, of course, we know where it all leads: to misery, starvation, death, the all but unbearable final scene of crying women."

B. Survivor Accounts:

See also: EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS on this website for a selection of brief quotations from survivors’ testimony.

1. Audio and/or Video Accounts:

~ Clips from the Mace Collection. a joint project of the Holodomor Research and Education Consortium and the Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre. 2014.

26 min. of audio excerpts from the original taped testimony presented during the U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine investigations in 1986. With English subtitles.

~ Share the Story 80 brief oral histories (most are less than 5 minutes) by survivors of the Holodomor currently residing in Canada. A project to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Holodomor. 2013.

~ Holodomor Survivors Tell Their Stories Canadian oral history project, presenting more than 50 videotaped personal accounts. Video accounts in Ukrainian; written English transcriptions. 2008-9

~Holodomor: 12 Holodomor survivors' oral histories A 26+ minute production. This web page also includes links to additional Holodomor testimony. Originally released as a CD by Canad Inns, Winnipeg: www.canadinns.com.

~ Children of Holodomor Survivors Speak This oral history project “consists of interviews with children of the survivors of the Ukrainian Holodomor (genocidal famine) and is the first … to address its impact on the lives of the second generation of survivors in the diaspora.” A project of the Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre, Toronto, 2015.

2. Written accounts:

~ U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine. Investigation of the Ukrainian Famine, 1932-1933; Report to Congress. Final Report, Appendix I Washington: U.S. GPO. 1988.

“Translations of Selected Oral Histories.” 160 pages of survivor testimony in English that appear in the original Ukrainian in the Commission’s Oral History Project

The First Interim Report and the Second Interim Report (print only) also include the translated testimony of scores of famine survivors.

~ Oral History Project of the Commission on the Ukraine Famine by James E Mace and Leonid Heretz.

Washington: U.S. G.P.O, 1990.

3 volumes consisting of hundreds of eyewitness and survivor testimonies. In Ukrainian with brief English summaries.

~ Witness: Memoirs of the Famine of 1933 in Ukraine, by Pavlo Makohon. Translated by Vera Moroz; originally published inAnabasis, Toronto. 1983. Engrossing memoir of the author as a 14 year old boy during 1933 and his efforts to survive. Short story length.

~ “Oleksandra Radchenko: Persecuted for her Memory,” by Volodymyr Viatrovych, in Lest we forget memory of totalitarism in Europe ; a reader for older secondary school students anywhere in Europe, ed. by Gillian Purves and Stephane Courtois. Praha: Inst. for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, 2013, pp. 264 – 271.

The diary entries of Oleksandra Radchenko, a teacher in Kharkiv at the time, offer a very rare sense of immediacy not found in accounts based on recollection. The primary source material is enhanced by an excellent summary of the events of the Holodomor by the author, as well as information about Radchenko’s fate upon the discovery of her diaries by the secret police.

~ The Black Deeds of the Kremlin: A White Book by Semen Pidhainy. Toronto: Ukrainian Association of Victims of Russian Communist Terror, 1953. v. 1: Book of Testimonies.

With the tragedy and privations of WWII just behind them, the recollections of these survivors and eyewitnesses are especially meaningful with regard to the unique horrors of the famine they experienced less than 20 years earlier.

~ The Ninth Circle: In Commemoration of the Victims of the Famine of 1933, by Olexa Woropay ( or Oleksa Voropai); with a brief forward by James E. Mace. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Univ., Ukrainian Studies Fund, 1983.

Includes the personal recollections of the author, as well as the brief recollections of eyewitnesses, all gathered between 1934-1948.

~ The Harvard Project on the Soviet Social System Online A searchable database of summary transcripts of 705 interviews conducted with refugees from the USSR during the early years of the Cold War. A quick search using the terms "famine 1933" yielded more than 100 transcripts by Ukrainians who mention or describe their experiences during the famine.

~ Ukrainian Famine Memoirs 32 brief written testimonies translated from the Ukrainian; [Originally published in Holod 33: Narodna knyha-memorial (Famine 33: National Memorial Book; Kyiv:1991]. Transcribed under the auspices of the Montreal Institute For Genocide and Human Rights Studies, Concordia University (Canada).

~ The Ukrainian Holodomor. Survivor Transcripts. Three brief accounts included in a collection of materials on the Holodomor held by the Australian newspaper, The Age. “Tanya” “Viktor” “Bozenna”

~ A Candle in Remembrance: An Oral History of the Ukrainian Genocide of 1932- 1933, by V.K. Borysenko. New York: Ukrainian National Women's League of America, 2010.

A collection of brief testimonies resulting from recent research conducted in Ukraine. Includes an informative, well-documented introduction as well as historical and contemporary photographs.

~ ‘Remember the peasantry’: A study of genocide, famine, and the Stalinist Holodomor in Soviet Ukraine, 1932-33, as it was remembered by post-war immigrants in Western Australia who experienced it, by Lesa Melnyczuk Morgan. ResearchOnline@ND, 2010. PhD thesis. University of Notre Dame, Fremantle, Australia.

Unlike most other accounts, excerpts of survivor memories create the narrative that makes up the main body of this thesis as it describes the early stages, execution, following events and societal effects of the Holodomor. Also includes an excellent overview of available research and resources in English.

~ Complex Social Memory: Revolving Social Roles in Holodomor Survivor Testimony, 1986-1988 by Johnathon Vsetecka.

Award winning paper presented at the Phi Alpha Theta Regional Conference, April 12, 2014, University of Wyoming, Laramie.

~Politics of perseverance : Ukrainian memories of "them" and the "other" in Holodomor survivor testimony, 1986-1988, by Johnathon Vsetecka. M.A. thesis, 2014. Univ. of Northern Colorado, Greeley, Colorado.

~ We'll meet again in heaven: Germans in the Soviet Union write their Dakota relatives 1925-1937, by Ron Vossler and Joshua J. Vossler. Fargo, N.D.: Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, North Dakota State University Libraries. 2001. For description and to order: https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/order/nd_sd/vossler2.html

Letters written by German colonists who originally settled in southern Ukraine and Moldova in the 19th c. describe a life becoming increasingly “desperate.” The publisher’s description concludes “…one senses imminent death, hunger, and fear… But readers will hear…the integrity of spirit of a people trying to survive in a world few of us can even imagine.”

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” ........George Santayana

"Please return the grain that you have confiscated from me. If you don’t return it I’ll die. I’m 78 years old and I’m incapable of searching for food by myself."

(From a petition to the authorities by I.A. Rylov)

"I saw the ravages of the famine of 1932-1933 in the Ukraine: hordes of families in rags begging at the railway stations, the women lifting up to the compartment window their starving brats, which, with drumstick limbs, big cadaverous heads and puffed bellies, looked like embryos out of alcohol bottles ..."

(as remembered by Arthur Kaestler, a famous British novelist, journalist, and critic. Koestler spent about three months in the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv during the Famine. He wrote about his experiences in "The God That Failed", a 1949 book which collects together six essays with the testimonies of a number of famous ex-Communists, who were writers and journalists.)

Our father used to read the Bible to us, but whenever he came to the passage mentioning ‘bloodless war’ he could not explain to us what that term meant. When in 1933 he was dying from hunger he called us to his deathbed and said “This, children, is what is called bloodless war...”

(as remembered by Hanna Doroshenko)

"What I saw that morning ... was inexpressibly horrible. On a battlefield men die quickly, they fight back ... Here I saw people dying in solitude by slow degrees, dying hideously, without the excuse of sacrifice for a cause. They had been trapped and left to starve, each in his own home, by a political decision made in a far-off capital around conference and banquet tables. There was not even the consolation of inevitability to relieve the horror."

(as remembered by Victor Kravchenko, a Soviet defector who wrote up his experiences of life in the Soviet Union and as a Soviet official, especially in his 1946 book "I Chose Freedom". "I Chose Freedom" containing extensive revelations on collectivization, Soviet prison camps and the use of slave labor came at a time of growing tension between the Warsaw Pact nations and the West. His death from bullet wounds in his apartment remains unclarified, though it was officially ruled a suicide. His son Andrew continues to believe he was the victim of a KGB execution.)

"From 1931 to 1934 we had great harvests. The weather conditions were great. However, all the grain was taken from us. People searched the fields for mice burrows hoping to find measly amounts of grain stored by mice..."

(as remembered by Mykola Karlosh)

"I still get nauseous when I remember the burial hole that all the dead livestock was thrown into. I still remember people screaming by that hole. Driven to madness by hunger people were ripping the meat of the dead animals. The stronger ones were getting bigger pieces. People ate dogs, cats, just about anything to survive."

(as remembered by Vasil Boroznyak)

"People were dying all over our village. The dogs ate the ones that were not buried. If people could catch the dogs they were eaten. In the neighboring village people ate bodies that they dug up."

(as remembered by Motrya Mostova)

"I’m asking for your permission to advance me any amount of grain. I’m completely sick. I don’t have any food. I’ve started to swell up and I can hardly move my feet. Please don’t refuse me or it will be too late."

(From a petition to the authorities by P. Lube)

"In the spring when acacia trees started blooming everyone began eating their flowers. I remember that our neighbor who didn’t have her own acacia tree climbed on ours and I went to tell my mother that she was eating our flowers. My mother only smiled sadly."

(as remembered by Vasil Demchenko)

"Of our neighbors I remember all the Solveiki family died, all of the Kapshuks, all the Rahachenkos too - and the Yeremo family - three of them, still alive, were thrown into the mass grave…"

(as remembered by Ekaterina Marchenko)

"Where did all bread disappear, I do not really know, maybe they have taken it all abroad. The authorities have confiscated it, removed from the villages, loaded grain into the railway coaches and took it away someplace. They have searched the houses, taken away everything to the smallest thing. All the vegetable gardens, all the cellars were raked out and everything was taken away.

Wealthy peasants were exiled into Siberia even before Holodomor during the “collectivization”. Communists came, collected everything. Children were crying beaten for that with the boots. It is terrifying to recall what happened. It was so dreadful that every day became engraved in my memory. People were lying everywhere as dead flies. The stench was awful. Many of our neighbors and acquaintances from our street died.

I have no idea how I managed to survive and stay alive. In 1933 we tried to survive the best we could. We collected grass, goose-foot, burdocks, rotten potatoes and made pancakes, soups from putrid beans or nettles.

Collected gley from the trees and ate it, ate sparrows, pigeons, cats, dead and live dogs. When there was still cattle, it was eaten first, then - the domestic animals. Some were eating their own children, I would have never been able to eat my child. One of our neighbours came home when her husband, suffering from severe starvation ate their own baby-daughter. This woman went crazy.

People were drinking a lot of water to fill stomachs, that is why the bellies and legs were swollen, the skin was swelling from the water as well. At that time the punishment for a stolen handful of grain was 5 years of prison. One was not allowed to go into the fields, the sparrows were pecking grain, though people were not allowed."

(From the memories of Olexandra Rafalska, Zhytomir)

"A boy, 9 years old, said: "Mother said, 'Save yourself, run to town.' I turned back twice; I could not bear to leave my mother, but she begged and cried, and I finally went for good."

(Recollected by an observer simply known as Dr. M.M.)

"At that time I lived in the village of Yaressky of the Poltava region. More than a half of the village population perished as a result of the famine. It was terrifying to walk through the village: swollen people moaning and dying. The bodies of the dead were buried together, because there was no one to dig the graves.

There were no dogs and no cats. People died at work; it was of no concern whether your body was swollen, whether you could work, whether you have eaten, whether you could – you had to go and work. Otherwise – you are the enemy of the people.

Many people never lived to see the crops of 1933 and those crops were considerable. A more severe famine, other sufferings were awaiting ahead. Rye was starting to become ripe. Those who were still able made their way to the fields. This road, however, was covered with dead bodies, some could not reach the fields, some ate grain and died right away. The patrol was hunting them down, collecting everything, trampled down the collected spikelets, beat the people, came into their homes, seized everything. What they could not take – they burned."

(From the memories of Galina Gubenko, Poltava region)

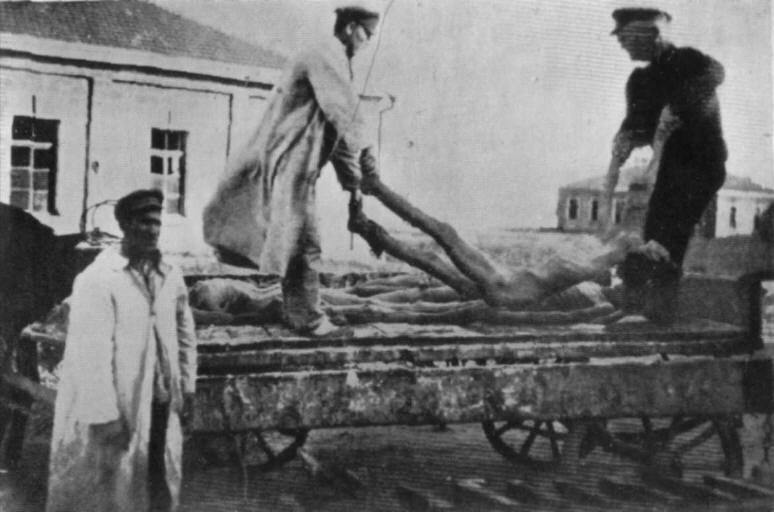

"The famine began. People were eating cats, dogs in the Ros’ river all the frogs were caught out. Children were gathering insects in the fields and died swollen. Stronger peasants were forced to collect the dead to the cemeteries; they were stocked on the carts like firewood, than dropped off into one big pit. The dead were all around: on the roads, near the river, by the fences. I used to have 5 brothers. Altogether 792 souls have died in our village during the famine, in the war years – 135 souls"

(As remembered by Antonina Meleshchenko, village of Kosivka, region of Kyiv)

"I remember Holodomor very well, but have no wish to recall it. There were so many people dying then. They were lying out in the streets, in the fields, floating in the flux. My uncle lived in Derevka – he died of hunger and my aunt went crazy – she ate her own child. At the time one couldn’t hear the dogs barking – they were all eaten up.”

........... Ukrainian émigré groups sought acknowledgment of this tragic, massive genocide, but with little success. Not until the late 1980's, with the publication of eminent scholar Robert Conquest's "Harvest of Sorrow," the report of the US Commission on the Ukraine Famine, and the findings of the International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine, and the release of the eye-opening documentary "Harvest of Despair," did greater world attention come to bear on this event. In Soviet Ukraine, of course, the Holodomor was kept out of official discourse until the late 1980's, shortly before Ukraine won its independence in 1991. With the fall of the Soviet Union, previously inaccessible archives, as well as the long suppressed oral testimony of Holodomor survivors living in Ukraine, have yielded massive evidence offering incontrovertible proof of Ukraine's tragic famine genocide of the 1930's.

The link below, provides plenty more website links, resources, article, eyewitness testimonies, memoirs, books, historical archive.............and much more..........