Why we can't talk about anything (important)

Over the years, I’ve noticed an increasingly disturbing trend. It’s becoming impossible to have a meaningful or productive dialogue anymore. And this isn’t just with strangers, this problem is now seeping into professional, casual and even personal relationships. It indicates there is a deep-rooted problem at the base of many other issues preventing real communication.

One of the first problems, which has been noted by others, is the fact that people simply can’t even agree to simple terms and parameters for discussion anymore. This is especially true of politically, religiously and ideologically charged subjects. While the definition of “fact” (when googled) is ostensibly “a thing that is indisputably the case,” in practice, pretty much anything is up for debate anymore. Further confounding the problem is the fact that statistics is a notoriously slippery discipline (and also notoriously misunderstood by the general populace) and most research today is funded to find a specific result (and as such, is not really unbiased.) Sometimes there can even be intentional obfuscation on an issue in order to keep the debate and division roiling – regarding the recent gun control controversy, I overheard on NPR the following quip while driving this morning that really just hits the nail on the head: “One thing missing in the debate on gun control recently? The data.”

The new dilemma

The new dilemmaRelated to this problem of a lack of agreement to terms and facts is that most people are untrained in the disciplines of determining truth, especially logical truth. Decrying the poor logic of public discourse, particularly online, is a bit of beating a dead horse at this point, but it really is a troubling trend. People don’t know how to determine whether arguments are sound or valid let alone true and they don’t particularly care. While my generation and presumably younger ones (I was born in 1988) were raised with this concept of “everyone is entitled to their opinion,” with good intentions, the concept has gone way too far and had a disastrously toxic effect on discourse. People can’t distinguish facts from opinions and moreover because everyone extends this “you’re entitled to your opinion” mentality to everyone in every situation (to include actual ARGUMENTS, which are different from OPINIONS), a nefarious sub-effect has developed wherein the general attitude seems to be “since everyone is equally entitled to their own opinion/argument, nobody can really be wrong, which means I can’t really be wrong, so why should I bother evaluating my own positions?” Whether you’re discussing the merits of entertainment media, art, or public policy, discourse has become a maddening chore.

In a recent back-and-forth on Facebook, a discussion over whether YouTube removing gun-related content on their platform was a violation of free speech (it’s not: “freedom of speech” is a legal protection of the constitution that restricts government censorship of your speech; Google and YouTube are not the government and are not beholden to let you say and do whatever you want on their platforms) somehow devolved to a conversation about whether Muslim restaurants not serving pork was discrimination deserving of equal legal consideration as the case of the cake shops refusing to serve homosexual customers. (Discrimination, by definition, refers to the differentiation in treatment between DIFFERENT CATEGORIES of people/things/etc, and when a given item [pork] is unavailable to EVERYONE, it cannot be discrimination. If we have the legal right to demand Muslim shops to serve us items that aren’t on the menu, then we would also have the legal right to demand Domino’s to serve us a Cheezy Gordita Crunch. It doesn’t make any sense.)

One underlying issue that’s going on is the increasing trend of personalizing politics. The phrase “identity politics” is quite telling, as people are literally tying their identities to their politics. Politics are becoming a new sort of religion as the more traditional religions are fading away in importance and relevancy to most of the public. And with that transformation comes the same sort of emotionally charged, dogmatic adherence to things poorly understood and poorly thought out. I’m sure many of us have had the experience of trying to debate a fervent missionary or street preacher (or have borne witness to this phenomenon), and that’s become the same type of task as talking about public policy with most young(er) people. People have rightly been very concerned with the religious invading the political, but now the political is essentially religious. When you’ve tied up your very identity into something, it’s unlikely you’re going to be unbiased in talking about the pros and cons of your position, and its even more unlikely you’re going to be reasoned out of your position.

The notion of “echo chambers” is a relatively recent phenomenon that is related to the maladies being discussed. People seemed surprised by the rise of, for example, alt-right Nazi movements or other “hate groups,” but haven’t thought about what’s pushing people to those groups. Many college campuses, workplaces, and other public spaces have essentially become echo chambers for the same type of views. This view tends to be anti-white and particularly anti-male. This is not a “boo-hoo, white men are victims” argument, but just a simple statement of fact – one need not look further than the recent controversy around Evergreen State College in Washington to see how extreme and yet widespread these views are becoming. I’m nearly 30 now, and I remember (as a white male) being exposed to this type of narrative as early as middle school. It only got worse in high school, and later college (despite a thankful and brief reprieve during my time in the United States Marine Corps). More than just being regarded as an “evil white male” (whether literally – feeling the seething hatred of peers who really felt and thought just that – or more abstractly – being taught about how white men had fucked the world up and how all of my own successes must actually be attributed to privilege regardless of any of the facts of my circumstances), my voice was silenced on more and more of the issues of the day due to precisely my biological sex and skin color. I couldn’t talk about oppression or basically anything to do with ethnicity because there was no way I’d understand. I couldn’t talk about equal opportunity, or the male-female wage gap, or virtually anything that wasn’t completely trivial (like entertainment media). And hell, in the modern day, we’re even seeing traditionally “safe” topics LIKE entertainment media becoming saturated with the same politically charged discussions (and thus the same disbarment from participating in those discussions) that exists in other topics. So when virtually every facet of society is telling you you’re a worthless (or worse than worthless: evil) piece of shit who can’t have an opinion on anything, is it really any surprise that young white men would begin cleaving to groups that aren’t telling them that? That, moreover, are telling them they actually do have value, do have worth, are capable of noble and great things? Now, understand, I’m not defending or even excusing Nazis or hate groups (though, this being the internet, I’m sure I’ll be taken out of context and accused of the very same), but much like any other echo chamber, people flock to these groups because it makes them feel good. We live in a society where somehow the way to “win” is to be the biggest victim, to see everyone else as an enemy who is assaulting you, and to draw a circle around “us” and condemn “them.” It’s what LGBT and feminist groups have been doing for a long time (constantly bickering about whether or not someone is a “true” ally or even having infighting about whether someone is a “true” feminist or whether someone is actually trans and so on) so why is it any surprise that white men would do the same thing? And, quite tellingly, Steven Pinker – a well known cognitive psychologist and author – recently discussed on an episode of the Joe Rogan Experience podcast how, most of the time, when these “alt-righters” (for lack of a better term) were engaged in respectful conversation, they can be easily talked out of their extreme and unreasonable positions. The problem is, we’ve all become so polarized that reasonable and respectful conversation is now the exception rather than the rule.

Many might point to the spread of various “liberal” (and I put the term in quotes because “liberal” and “liberalism” have actually become some kind of Orwellian double-speak terms whose meanings in practice have nothing to do with the meanings commonly held in the mind of most people) policies and agendas, in particular certain aggressive strains of academic feminism and the tenets of political correctness as the source of what’s gone and is going wrong. While it’s true that these philosophies have had an insidious effect, and it might be worthwhile to discuss some of the particulars, that conversation has been happening around various parts of the web for a long time now (gaining a lot of traction in 2009 and only heating up since then) and there’s plenty of information about it for those interested elsewhere.

One thing that needs to be stated here, and that isn’t talked about enough, is the fact that none of this is really new. People feel like it is new, insist that it is new, but history begs to differ. This isn’t the first time women have fought for (and been attaining) equal rights, or the first time sexual morals have been revolutionized, or the first time religion has fallen out of favor in society at large. John Bagot Glubb wrote a fascinating treatise entitled “The Fate of Empires” which traces the themes of expansion and decline of the world’s largest known civilizations to point out all of the similarities. It’s quite an eye opening read. And this idea that we haven’t learned from history is an idea as ancient as history itself; the ancient document of Ecclesiastes from the Old Testament opens with the author (generally regarded to be King Solomon, an ancient Jewish King renowned for his wisdom) bemoaning people’s lack of learning from those that came before: “That which has been is what will be, that which is done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun. Is there anything of which it may be said, “See, this is new?” It has already been in ancient times before us. There is no remembrance of former things, nor will there be any remembrance of things that are to come by those who will come after.” It seems failure to learn from history is a trope as old as history itself.

I didn't create this image or write the text but I'm sure the highlighted bits are bound to rustle some jimmies

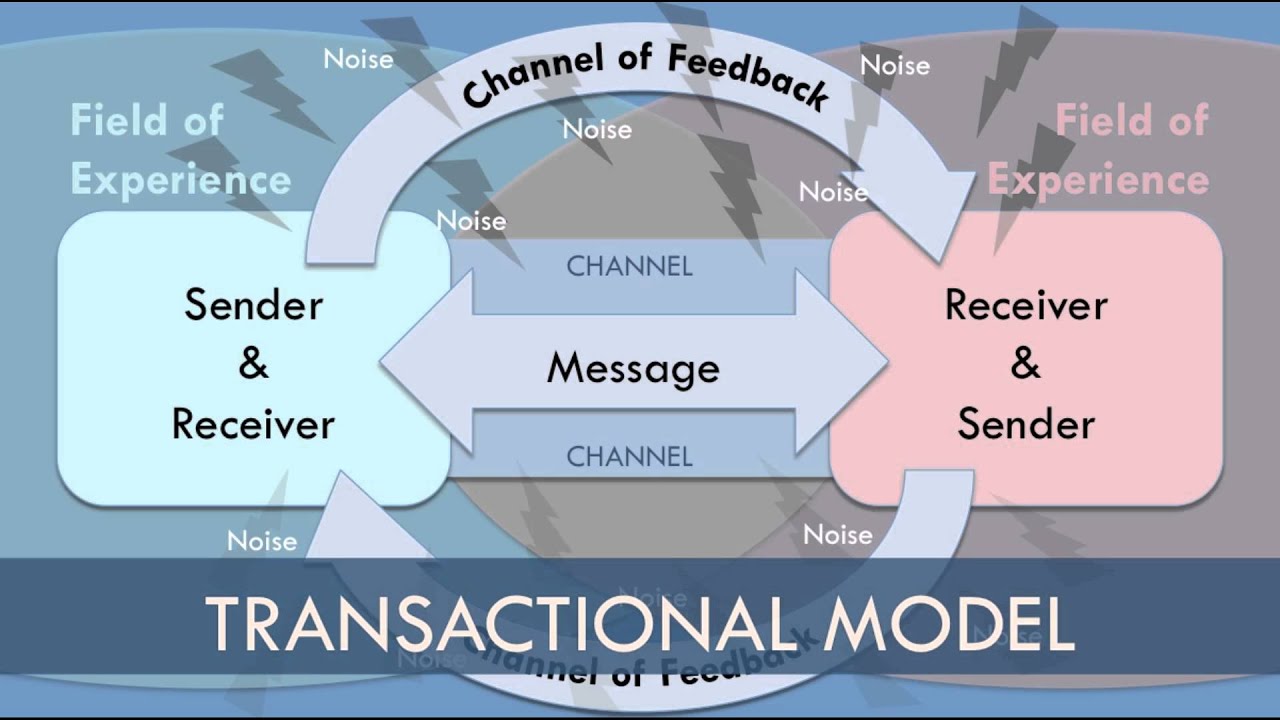

I didn't create this image or write the text but I'm sure the highlighted bits are bound to rustle some jimmiesAnd maybe that has to do with what I propose to be the real root order cause of it all. Here’s the thing – we know from studying human communication that a person constructs their reality based upon what they decode from whatever messages have been encoded to them. While improvements in encoding can be important (that is to say, it’s important to think before you speak, to write carefully and clearly, and so on and so forth), the fact of the matter is that any objective truth or merit of any given encoding (including the process of decoding natural laws etc through the process of science – that is to say, decoding the encodings of natural phenomenon) is SUBSERVIENT to the subjective or relative truth of any particular person’s decoding processes. If this doesn’t sound very, very troubling, it ought to. Any number of biases processes can distort what would otherwise be an objective truth or reality to something completely incongruent with the truth, and because of this phenomenon, many have questioned whether there can really even be an objective truth to begin with. And if there can’t be an objective truth, then why should your argument be any better than my argument? (We see here a repeat of the theme raised above, when discussing opinions and arguments.)

Language and our language faculties in general may, in fact, be the culprit. A while back I wrote an essay on the entwinement of language and thinking, which delved into many aspects of language theory. When you get to the heart of it, the major differences people point to as starting conflict (things like ethnicity or national pride or anything else) may have, at their base, been due to differences in language. I suggest you take a look at the section on Language Ideologies in the essay above. Of import here, I reiterate from that essay the following:

[T]he entire system [of language ideologies] is imposed right under our noses. It begins in the classroom: “Standard language ideology is a basic construct of our elementary and secondary school’s approach to language and philosophy of education. The schools provide the first exposure to SL ideology, but the indoctrination process does not stop when students are dismissed” (Lippi-Green, 1994)… After the school system, there are several other guardians of standard language ideology…: “…the educational system, the news media. the entertainment industry, and what has generally been referred to as corporate America. At the end of the article, I argue for adding the judicial system to this list” (Lippi-Green, 1994).

What does this really mean? It means arriving at a solution to gun control, to LGBT rights, to abortion, to any other charged issue of the day is a bigger problem than just the factual particulars of that issue (given what we already know about the difficulty of agreeing to what the facts are in the first place). With so very many things out of whack in our modern society, with “mental illness,” (I put “mental illness” in quotes because that’s a whole separate quagmire of misunderstandings and poor solutions) dissatisfaction, and even hopelessness on the rise, one has to wonder whether we are dealing with a million individual problems or if we aren’t in fact dealing with the symptoms of one much larger, unifying problem. Our ability to communicate is fundamental to being human, and we are taking it fundamentally for granted. Understanding the communication process – noise, feedback, biases, encoding, decoding – and realizing the benefits and pitfalls is central to resolving other issues. Realizing that what you heard may not have been what the person said (that is to say, the message you decoded is not the message they intended to encode) – even if you can repeat their exact words back to them with 100% accuracy – is an example of what a more sophisticated understanding of communication could bring us. And until we reach the point where we are actually communicating with each other rather than to or at each other, we are only going to continue to see the rise of extremism in all facets of life – whether they be political, religious, or ideological.